Pit and Pendulum: A Cinematic Experiment

Editing is the key to cinema.

When I first read Poe’s story about a prisoner being tormented by unseen jailers, I visualized it. I saw the prisoner, the cell, the pit, the fiery walls, all quite vividly in my mind’s eye.

For that is the power of well crafted words, they provide brushes for the reader’s imagination to paint with.

Cinema can do the same, yet few filmmakers are able to restrain themselves from papering over everything.

“By offering an incomplete image or process, Poe involved his readers in the creative process in a way that Baudelaire, Valery, T. S. Eliot, and many others have admired and followed. Poe had grasped at once the electric dynamic as one of public participation in creativity. Nevertheless, even today the homogenized consumer complains when asked to participate in creating or completing an abstract poem or painting or structure of any kind. Yet Poe knew even then that participation in depth followed at once from the telegraph mosaic.” Marshall McLuhan – Understanding Media (1964)

Poe’s story is the perfect vehicle to demonstrate this in cinema.

The Pit and the Pendulum is a first person narrative with no onscreen dialogue which means the narrator and the prisoner can be different people.

The power of the concept comes from using cinema techniques to influence the Viewer’s imagination, so the less shown, the better.

Consider the famous shower scene in Psycho. Many believed they saw the knife puncture the flesh, the moment was so powerful, yet every student of cinema knows the knife never punctured anything.

How is the Viewer made to imagine they are seeing something that is not there?

Consider the opening scenes of Jaws when the girl is attacked by the shark. The Viewer imagines what is happening beneath the water and the moment is all the more horrifying because of it.

27 minutes.

A wide shot of darkness, one person, the Prisoner, clad in simple grey pajamas, is lit by a single pool of light. There are no details or textures, it is simply blackness surrounding her.

The Prisoner stands looking up listening while unseen judges pass sentence, as told by Poe’s Narrator. Silhouettes of candles represent the judges.

After sentencing the Prisoner passes out and finds herself transported to a dark dungeon.

She gropes her way around blindly, and while pacing out the size of her cell, stumbles, falling at the edge of a circle of light – the edge of the pit she almost stepped into.

We look up at her looking down while the narrator describes her conjectures about what might be waiting for her in the pit.

The Prisoner backs herself into a corner and huddles there determined not to move. She passes out again.

The Prisoner’s thoughts upon re-awakening to discover herself strapped down on her back and her ensuing observations of her surroundings, the discovery of the rats, and then of the Pendulum, are narrated while we study her from multiple angles.

Many elements together make this sequence terrifyingly real:

a GUST of air to disturb her hair when the blade passes close;

the SOUND of heavy gears moving during the swing;

a rhythmic WHOOSH which grows in presence as the blade descends,

the WHISTLE of its steel when it is passes closest;

pendulum POV shots swinging over the Prisoner,

and ACTING skills

all provide depth and texture, working together to transport the Viewer into the claustrophobic, mind-wrenching world of Edgar Allan Poe.

To get that kind of involvement, that kind of commitment, from the Viewer, requires effective use of every cinematic technique at our fingertips, lighting, cinematography, acting, Foley, editing, etc., to provide enough sensory imprints with which the Viewer can construct a personalized setting for the horrifying events.

The massive pendulum mechanism is made from the movement of shadows and flashes of light which provide the framework for the Narrator’s words.

The Viewer is the architect of the dungeon, its smells, its textures, and will create far more terrifying images than any that can be built.

Elwy Yost

The roots of this was a project Elwy Yost and I were working on. He wanted to narrate classic stories in the public domain and add simple visuals as illustrations. Although the project did not get the greenlight one of the stories we planned to do stuck in my mind.

A story narrated by the victim of unseen tormentors.

“In the confusion attending my fall, I did not immediately apprehend a somewhat startling circumstance, which yet, in a few seconds afterward arrested my attention. It was this: my chin rested upon the floor of the prison, but the upper portion of my head touched nothing. At the same time, my forehead seemed bathed in a clammy vapor, and the peculiar smell of decayed fungus arose to my nostrils. I put forward my arm, and shuddered to find that I had fallen at the very brink of a circular pit.”

Narration that is as terrifying as any imagined horror.

“I quivered in every nerve to think how slight a sinking of the machinery would precipitate that keen, glistening axe upon my chest. I saw that some ten or twelve vibrations would bring the steel in actual contact with my robe — and with this observation there suddenly came over my spirit all the keen, collected calmness of despair.”

With a little judicious editing of a few dated references, the story becomes universal, timeless, it could take place in 1843, 1943, or 2043.

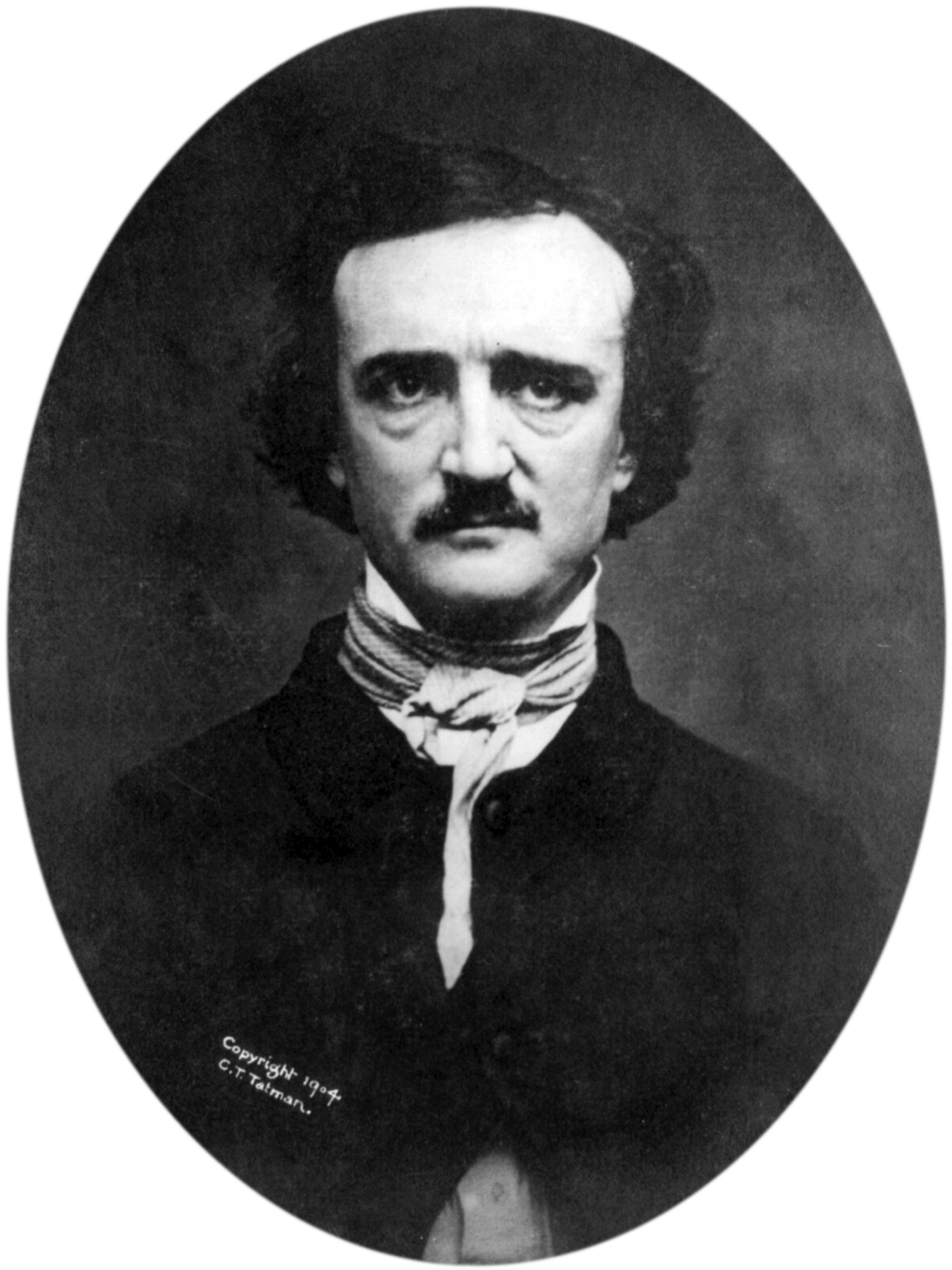

Poe

Edgar Allan Poe’s name has proven staying power and interest. His works have been international classics since the 19th century.

He is respected as a respected American author in both literary and popular circles so there will be interest.

As Elwy saw it, this is about illustrating a classic rather than re-interpretating it.

Needs.

It waits upon timing, funding, and an actor skilled in body movement.